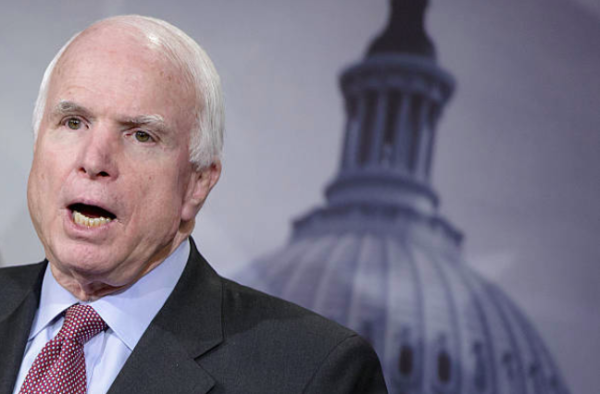

In the middle of the memorials and remembrances, in the middle of the public viewings and the televised liturgies, in the middle of the extended media coverage, it was hard to speak to a deeper sense of John McCain’s life.

It was also, in my mind, unwise to say anything beyond something brief, mild, and uncontroversial.

In the immediate aftermath of a death of an important yet complicated public figure, the rush to establish a legacy or identity is fierce and pronounced. Even on MSNBC, the supposed “liberal” cable news network in the United States, a slickly-produced “Thank You” note appeared on weekday programming, plainly linking the network with a view of the person it was covering.

I am not here to litigate the legacy and career of John McCain. The purpose of this column — after a three-week break caused by the United States Open tennis tournament, which I covered for a website — is to establish how we should talk about significant men and women in the political arena when they die.

In the coming years, we will witness the deaths of George Herbert Walker Bush, Jimmy Carter, and Henry Kissinger, among others. How should we process when these and other influential people leave public life through the ultimate — and eternal — portal? It seems like an important question for a mature society to contemplate and wrestle with.

I would like to offer a few basic pointers.

First, media outlets should not be producing televised “Thank You” notes to these public figures. Every public figure’s life resonates differently among various people. It is up to the television viewer to decide how to view the public figure who just died. It is up to the media outlet, in the broadcast realm or in print, to tell viewers or readers all the salient facts about the person’s life.

This should be obvious, but in an American media ecosystem now dominated by ideological programming, the idea of simply opening up the book of a person’s life and calmly noting what John McCain did in politics and military service — regardless of whether it flattered him or made him look bad — is a foreign concept.

When future generations study our time — much as we studied the Civil War, or the Great Depression, or World War II when we were kids — they will want to know why public figures did what they did. They will want to know about their successes, their failures, their complexities, and their toughest decisions.

Media outlets should dissect John McCain’s decades in public service — not to shame and not to praise, but to merely give viewers a full account of his life as it was, not as any ideological viewpoint might want it to be. Young people deserve the truth of a person’s life — not hatefulness, but not apologia, not harshness, but also not hagiography.

Lives are complicated. Media outlets should be devoted to exploring a politician’s complexities in his moment of death, not to painting a portrait as the cable news networks did.

What the media does obviously harms citizens’ efforts to sift through the mythmaking (or the knee-jerk eviscerations). Yet, how should citizens try to process the life of John McCain or the other politicians who will soon die?

- If you don’t have anything nice to say about the person, say nothing. The internet is full of hate as it is.

- If you disapprove of a public figure’s actions or legacy, turn fire-breathing condemnations in a moment of death into something more constructive. Explain why the person’s failures or misguided views can educate current or future generations. Use the flawed life (if you think that way about the person who just died) as a teaching tool, not as a way to score political or ideological points.

- Acknowledge how or why a person might have taken a wrong turn in life. John McCain went through a highly traumatic and prolonged experience as a prisoner of war. Appreciate how that might scar a human soul and lead to views and actions which might not have agreed with your own. Be compassionate to those who have suffered, especially when that suffering led to actions you did not agree with or approve of.

- Acknowledge risks taken or prices paid by the person. I am firmly anti-war, but John McCain went through the hell of war. He took a risk and paid a price I did not. If I had also served in a war, I might be able to think of McCain differently, but he speaks from firsthand experience. I wish that his experience of war led him to an anti-war view, but he owns “authority of experience” I lack. This doesn’t make him right, but it does mean I can’t criticize him from the bleachers. Not when he owns a traumatic moment I can’t ever know about.

- A person is not as great as his best moment and not as bad as his worst moment. John McCain’s life, like the lives of other people who serve in government and politics for a long time, is complicated. If you hear someone say his life is easy to summarize and requires no deeper examination, that person is almost certainly invested in wanting you to see the world through an ideological prism rather than through the one prism which matters: the truth, all of it, unvarnished.

Main Photo:

Embed from Getty Images